Return To Home Page

Return To Home Page

Table of Contents Page

Table of Contents Page Return To Home Page Return To Home Page

|

Back to the  Table of Contents Page Table of Contents Page |

Contents of This Page |

STRINGED INSTRUMENTS... at least some of them...HARPSWhat did they look like? ... and what evidence is there for that?

| ||

HARPS

HARPSYou're right by them! | |||

FIDDLES etc. FIDDLES etc.

| |||

PSALTERY

PSALTERY | |||

DULCIMER

DULCIMER | |||

TO The OTHER STRINGS PAGE

TO The OTHER STRINGS PAGE |

|

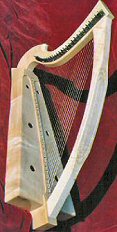

The body, or sound box, was and still is usually of wood. Parts of it were sometimes made of bone, the tuning pegs, for example. Sometimes they would use animal skin for the sound board - the wide bit that has the strings fastened to it. Ancient Welsh harps used this. The harp here has a pillar, as do most harps. Really early harps, like some Egyptian ones in the British Museum, had no pillar but relied on the strength of the wood not to bend too much. Obviously you couldn't pull the strings too tight! A modern orchestra harp has about 4 tons of strain on it when all the strings are tight. That's about as much as the weight of two Landrovers. |

|

Harps normally have one row of strings, and these often play similar notes to the ones you get by playing up the white notes of a modern keyboard. (Note to harp freaks - yes, I know lever harps are usually tuned in Eb, but let's keep it simple!) You can easily see from the picture of my "Kinellan" clarsach on the right that there's one row of strings up the middle of the soundboard. OK, fine, as long as you're happy just playing those notes. You can make cunning ways of tuning a few surprises in, but you're still stuck with the notes you have. Some tunes move onto different notes which aren't available like this. |

|

|

|

So here's one solution. Here you see a modern copy of an Italian double harp, an "Arpa Doppia". You can clearly see from the black button like pegs on the soundboard it has two rows of strings. So the cunning harp player has one row tuned to the piano keyboard white notes, and the other row to the black notes. All you have to do is reach inbetween the strings for the extra notes. Sounds simple? You should try it! On the right you can see the two rows of tuning pegs, set on different layers of the wood. It's quite hard tuning that lot too. |

|

|

Dear reader, in the cause of research, I travelled to Belgium where, in Brussells, there's a fantastic museum of instruments. Not that I enjoyed the trip at all, you understand... the things I do just to be helpful... On the left you see a rather wobbly picture of an early Italian double harp. I'm sorry it's a bit wobbly: I was working without flash light & trying to hold the camera still! But you can still see the two rows of pins up the middle. On the right you can see the Spanish answer to the problem. You cross the strings over & reach a bit higher or a bit lower to play the different notes. You can see the strings crossing quite nicely on this picture. You can also see that the harp has a bigger, fatter body - producing more sound. |

|

If you want to see more pictures of harps and other instruments made by George Stevens, who made my Queen Mary clarsach, look at his website:

http://www.btinternet.com/~george.stevens

If you want to see more pictures of harps and other instruments made by George Stevens, who made my Queen Mary clarsach, look at his website:

http://www.btinternet.com/~george.stevens Return to top of this page.

Return to top of this page.

|

Here is one Pigs snout psaltery, viewed the un-pig way up. |

|

Here it is, looking more like a pig's nose, if you have a strong imagination; this is why it's called the "porco" in Italian. I am reliably informed by many hundreds of pupils at many schools that it looks more like a pair of underpants. ... True, but underpants were not always very fashionable in an age when clean laundry wasn't always easily available, so they'd seen more pigs than pants. |

|

|

Here is a pane of glass from Shibden Hall, near Halifax. There are some other pictures of parts of this same window elsewhere on this site, so if you've met this explanation before skip over this bit. During the late 1500's, glass from Churches in York, which were having their decoration smashed up following Henry VIII's Reformation, some medieval glass was rescued and put into this window at Shibden Hall. So this picture is about 700 years old. OK, you can stop skipping! The picture here is of a bird sitting on what seems to be a cross between a box and a pigs snout psaltery. Whatever it was based on, it looks a lot like the instrument I have. |

Reproduced with permission |

| ... and here's one painted by Dante Gabriel Rosetti, in Victorian times. Though there was a great Victorian fashion for recreating medieval themes, the artists didn't always get it right! This psaltery is very pretty and quite useless. Since the strings simply stretch round the corners of the instrument and don't have anything like bridges to hold them up, all you'd get would be a dull slapping sound. Try it with a rubber band across a box and you'll have it perfectly. Though I suppose that since the painting is called "The Merciless Lady" it might just be that she's mercilessly making her man listen to the awful noise she's making and then asking "Darling, don't you just love my music?"... ?? |

|

Return to top of this page.

Return to top of this page.

View Dulcimer Pictures

This instrument came to Europe from Arabic countries. It's still played

there, with central bridges, where it is called the santur, sometimes spelt santoor. A very similar instrument in the same family has no central bridges, it is plucked, and is called the qanun. I've also seen this spelt as qanoon. Since these are Arabic words I'm not going to argue how they ought to be reproduced in English!

(I'm very grateful to Pav Verity of Edinburgh for putting me right with some of the details of which instrument is which here.)

There are many more instruments in the family, in different countries, for example:

View Dulcimer Pictures

This instrument came to Europe from Arabic countries. It's still played

there, with central bridges, where it is called the santur, sometimes spelt santoor. A very similar instrument in the same family has no central bridges, it is plucked, and is called the qanun. I've also seen this spelt as qanoon. Since these are Arabic words I'm not going to argue how they ought to be reproduced in English!

(I'm very grateful to Pav Verity of Edinburgh for putting me right with some of the details of which instrument is which here.)

There are many more instruments in the family, in different countries, for example:

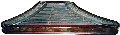

My nearly-Victorian dulcimer was made by Frederick Barley in London. It was made in 1902, but it

is just the same style as those made while Queen Victoria was still alive.

It's the sort of instrument you might find being played on the street,

in the pub, or in ordinary people's houses.

You would not normally find "nobs and toffs" playing one.

|

|

I also have a small dulcimer copied from medieval and Tudor period pictures. You can see it on the pictures page too.

The strings on dulcimers are in groups or courses. On my medieval dulcimer there are two to each course. On Frederick Barley's, there are 4 to each course,

and each course goes over a bridge.

Where they are made this way they're called

chess pieces

On some strings you get different notes by playing

different sides of the chess pieces. This isn't a very good picture of some of the chess pieces on the instrument in the

main picture. The really neat part about using bridges part way along the strings is that you get more notes for the same amount of strings, and so can cram more notes into less space. This lets you have a smaller box to carry about, and also means you haven't got to move your hands so far to play the different notes. Cunning!

LINKS TO FIND MORE:

LINKS TO FIND MORE:

http://www.s-hamilton.k12.ia.us/antiqua/dulcimer.htm - a good site showing lots of other instruments too. I'm advertising the competition here!

http://www.aramusic.com/history.htm Dulcimers in arabic music

Return To Home Page Return To Home Page

|

Return to top of this page. Return to top of this page.

|